Why is there so little extra care housing in the UK? It’s not for lack of evidence about its benefits.

Why is there so little extra care housing in the UK? It’s not for lack of evidence about its benefits.

In 2019, The King’s Fund was asked by the Department of Health and Social Care to scope options for an evaluation of any future Care and Support Specialised Housing (CASSH) funding tranches that might be issued. The scheme provides capital funding to build new specialised housing in England for older people and disabled adults with care and support needs (it therefore includes but is somewhat broader than ‘extra care’).

The work was specifically not an evaluation but rather a scoping exercise to explore areas that an evaluation might want to cover, such as the established benefits of CASSH-type housing, including extra-care, the wider health and care policy goals to which CASSH-type housing might be expected to contribute, and how these might be measured in a future evaluation.

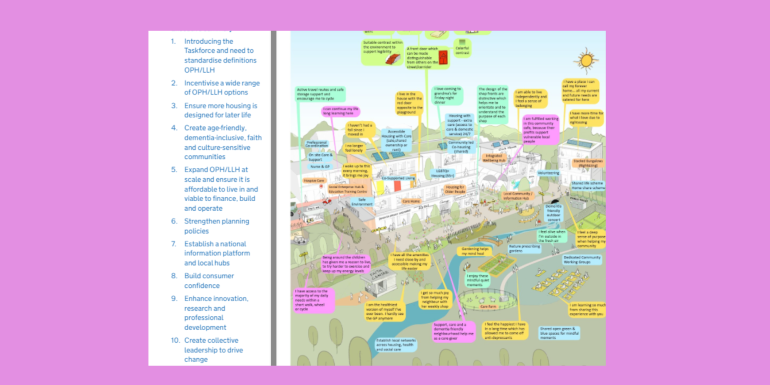

As it turned out, the report of our short scoping exercise found a long list of evidence about the effectiveness of extra care housing. Much of it came from a range of already-published studies on issues such as potential savings to healthcare services, reduced social care spending, improvement in people’s personal health, improvement in people’s mental wellbeing, usage as community anchor and as a generator of efficiency in the wider housing market.

In addition, providers who had benefited from CASSH funding identified other potential benefits that we hadn’t found in the literature. These included:

- the ‘opening up’ other care spaces for people with greater need – those who move to extra care may free up spaces in other care services

- the cost equivalent of providing residential and nursing care

- the benefits of having care providers on site to identify health issues earlier

- ‘softer’ issues such as companionship and outdoor space and availability of activities such as reminiscing sessions

- local extra care housing meaning people need not move away from where they have lived and can retain social connection.

The range and extent of the existing evidence led us to suggest that repeating this evidence-gathering exercise might not be necessary in a subsequent evaluation (though we suggest that a systematic review might have some value). We did however note that existing evidence is mainly for extra care housing and older people rather than for people with learning disabilities or mental health problems (both of whom are covered by the CASSH programme) so more work might be needed in these areas.

More broadly, our findings add to the ongoing debate about why extra care housing remains such a small part of the market in the UK compared to some other countries. We know that in Australia, New Zealand the United States over five percent of over-65s live in extra care developments compared to less than one percent in the UK.

The discrepancy has been widely discussed and there are a wide range of suggestions about the factors behind it. Exploring these was well beyond the remit of our short scoping exercise but it should, at least, help rule out lack of evidence for the benefits of extra care as one of them. Our report suggests that, on the contrary, there is ample evidence for the benefits of extra care housing to residents and to the wider health and care system, and that it has a wider potential role in a health and care prevention agenda.